When Microsoft gave its 2,300 employees in Japan five Fridays off in a row, it found productivity jumped 40 per cent.

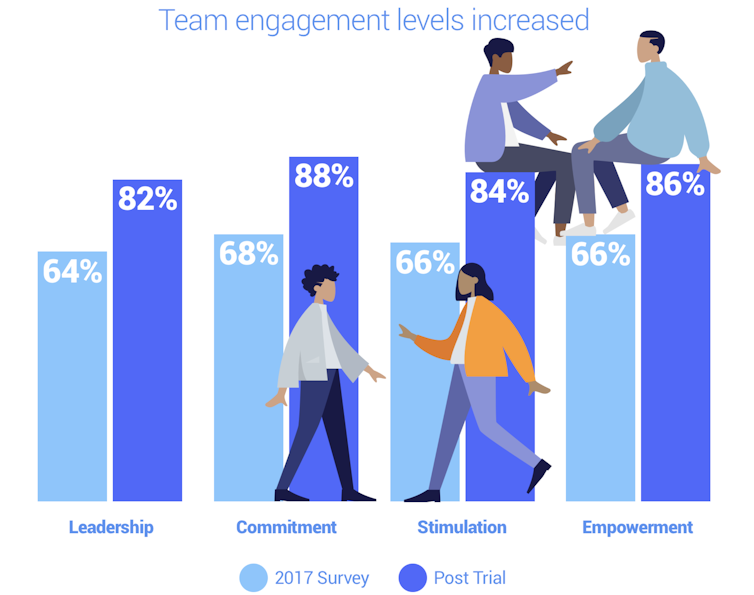

When financial services company Perpetual Guardian in New Zealand trialled eight Fridays off in a row, its 240 staff reported feeling more committed, stimulated and empowered.

Around the world there’s renewed interest in reducing the standard working week. But a question arises. Is instituting the four-day week, while retaining the eight-hour workday, the best way to reduce working hours?

Arguably, retaining the five-day week but cutting the working day to seven or six hours is a better way to go.

Shorter days, then weeks

History highlights some of the differences between the two options.

At the height of the Industrial Revolution, in the 1850s, a 12-hour working day and a six-day working week – 72 hours in total – was common.

Mass campaigns, vigorously opposed by business owners, emerged to reduce the length of the working day, initially from 12 hours to ten, then to eight.

Building workers in Victoria, Australia, were among the first in the world to secure an eight-hour day, in 1856. For most workers in most countries, though, it did not become standard until the first decades of the 20th century.

The campaign for shorter working days was based largely on worker fatigue and health and safety concerns. But it was also argued that working men needed time to read and study, and would be better husbands, fathers and citizens.

Reducing the length of the working week from six days came later in the 20th century.

First it was reduced to five-and-a-half days, then to five, resulting in the creation of “the weekend”. This occurred in most of the industrialised world from the 1940s to 1960s. In Australia the 40-hour five-day working week became the law of the land in 1948. These changes occurred despite two world wars and the Great Depression.

Stalled campaign

In the 1970s, campaigns for reduced working hours ground to a halt in most industrialised countries.

As more women have joined the paid workforce, however, the total workload (paid and unpaid) for the average family increased. This led to concerns about “time squeeze” and overwork.

The issue has re-emerged over the past decade or so from a range of interests, including feminism and environmentalism.

Back on the agenda

A key concern is still worker fatigue, both mental and physical. This is not just from paid work but also from the growing demands of family and social life in the 21st century. It arises on a daily, weekly, annual and lifetime basis.

We seek to recover from daily fatigue during sleep and daily leisure. Some residual fatigue nevertheless accumulates over the week, which we recover from over the weekend. Over longer periods we recover during public holidays (long weekends) and annual holidays and even, over a lifetime, during retirement.

So would we be better off working fewer hours a day or having a longer weekend?

Arguably it is the pressure to fit family and personal commitments into the few hours between getting home and bedtime that is the main source of today’s time-squeeze, particularly for families. This suggests the priority should be the shorter working day rather than the four-day week.

Sociologist Cynthia Negrey is among those who suggest reducing the length of the workday, especially to mesh with children’s school days, as part of the feminist enterprise to alleviate the “sense of daily time famine” she writes about in her 2012 book, Work Time: Conflict, Control, and Change.

Historical cautions

It’s worth bearing in mind the historical fall in the working week from 72 to 40 hours was achieved at a rate of only about 3.5 hours a decade. The biggest single step – from six to five-and-half days – was a reduction of 8 per cent in working hours. Moving to a six-hour day or a four-day week would involve a reduction of about 20% in one step. It therefore seems practical to campaign for this in a number of stages.

We should also treat with caution results of one-off, short-term, single-company experiments with the four-day week. These typically occur in organisations with leadership and work cultures willing and able to experiment with the concept. Employees are likely to see themselves as “special” and may be conscious of the need to make the experiment work. Painless economy-wide application cannot be taken for granted.

Anthony Veal, Adjunct Professor, Business School, University of Technology Sydney

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Add Category

Add Category