Australia has joined New Zealand, the United States, Indonesia, India, Israel and other countries in deciding to refuse entry to all foreigners flying from or who have recently been in mainland China.

These bans dramatically escalate the potential economic impact of the novel coronavirus.

Over the past two decades China has grown from a minnow to a whale in international travel. Not counting mainland Chinese visiting Hong Kong and Macau (about 76 million in 2018), data from the United Nations World Tourism Organisation show the number of Chinese going abroad climbed from 2.8 million in 1997 to about 73 million in 2018.

This places China fourth in terms of international visits, behind Germany (about 92 million), the United States (88 million) and Britain (74 million).

Rise of the Chinese traveller

Besides Hong Kong and Macau, Chinese travellers most visit neighbouring nations – Thailand, Japan, Vietnam, South Korea and Singapore. Next is Italy, then the United States and Malaysia.

Australia is somewhat down the list – just the 17th-most-popular destination for Chinese visitors in 2018 (1.4 million visits). New Zealand was the 26th (about 448,000).

But China is now Australia’s largest source of international visitors. Short-term arrivals from China overtook those from New Zealand (the top source for many decades) in 2017.

In the 12 months to November 2019, there were 1.44 million Chinese visitors to Australia, according to Tourism Australia. This was about 15% of the total 9.44 million short-term arrivals.

But Chinese visitors contributed relatively more to the Australian economy. The average spend per Chinese trip was $A9,235. This compared with $A5,943 for Germans, $A5,219 for Americans, $4,614 for Japanese and $A2,032 for New Zealanders.

This meant Chinese travellers contributed about A$12 billion to the Australian economy – or 27% of the total amount spent by all international visitors. International tourism accounts for about a quarter of Australia’s total tourism market. That means, in the greater scheme of things, Chinese travellers help create 0.6% of Australia’s annual GDP.

The student effect

The reason the Chinese spend (on average) so much more than other visitors is due to the large number of Chinese who come to Australia to study.

The Tourism Australia data show almost 275,000 of the 1.44 million Chinese visits – about 20% – were for educational purposes. By comparison, study was the reason for fewer than 14,000 – or less than 1% – of the 1.42 million visits by New Zealanders.

Chinese students stayed an average of 124 nights before going home and spent an average of $27,000. This is more than any other nationality. The average spent by all international students was A$22,000.

Chinese tourists, on average, stayed an average of 14 days and spent A$4,655. The average for all international holidaymakers was A$4,286. The biggest-spending were the Italians (A$7,174), Germans (A$6,028) and British ($A6,011).

So Chinese students accounted for just shy of 58% – or A$7.1 billion – of all the money spent by Chinese visitors.

Ban impacts

Australia’s travel ban has come just in time to disrupt the plans of thousands of Chinese students coming or returning to Australia. February is normally the peak month for Chinese arrivals in Australia. In 2019, the month recorded 206,300 arrivals – roughly double the average month.

This is because this month is when many Chinese students arrive or return to Australia to start the university year. (It’s also due in part to the proximity of the Chinese lunar new year – January 25 this year, February 25 last year – when hundreds of thousands of Chinese travel for a holiday or to visit family.)

Chinese students enrolled in Australian universities comprise 38% of all full-fee paying international students. With international students now contributing about 23% of university revenues, this suggests the Chinese market alone contributes about 9%.

More Chinese students come to Australia for vocational education and training or school. All up, Chinese students account for about 30% of total overseas student enrolments.

Long-term impacts

Our main point of reference for the economic impact of the coronavirus is the impact of SARS in late 2002. The Chinese government imposed similar travel restrictions to now. But Australia did not ban travellers from China outright. It instead relied on screening at airports.

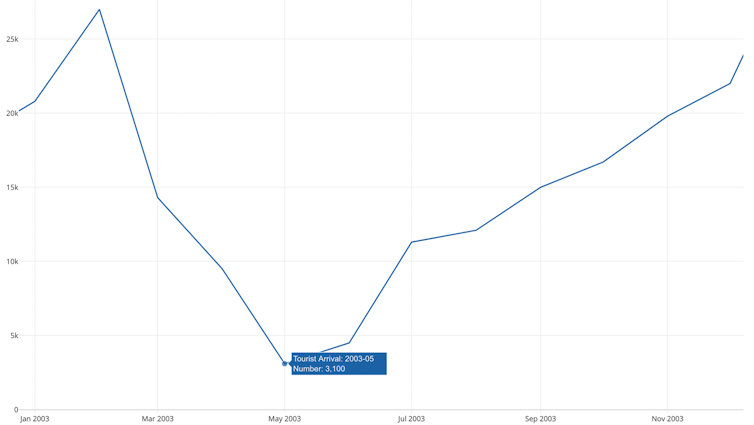

In May 2003 just 3,100 Chinese visited Australia, a 75% decline on the 12,600 visitors in May 2002. Visitor numbers from other Asian countries also suffered, with the total number of international short-term arrivals falling 8.5% in April , then a further 2.6% in May.

But SARS was contained relatively quickly. By July the Chinese government had lifted its restrictions. The following month Chinese arrivals were back up to more than 12,000.

The economic impact of SARS was therefore “short-lived and limited”, according to the Australian Treasury.

The economic impact of the novel coronavirus is shaping to be more signficant, based on the scale of crisis, the severity of travel restrictions, the likelihood travel bans will stay in place for longer and the much greater numbers of Chinese tourists and students on which Australia’s tourism and education industries have come to rely.

Author:Mingming Cheng, Senior Lecturer, School of Marketing, Curtin University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Add Category

Add Category