Ancient microbiota information represents a vital resource to study bacterial evolution and explore the biological spread of chronic diseases throughout history.

An international team of researchers analyzed microbial DNA found in indigenous human paleofeces (desiccated excrement) from dry caves in northern Mexico and Utah. They found that the ancient human gut microbiome is similar to those of modern-day people from non-industrialized populations.

The study, published in the journal Nature, is the first one to reveal novel species of microbes in the specimens.

Ancient microbiome

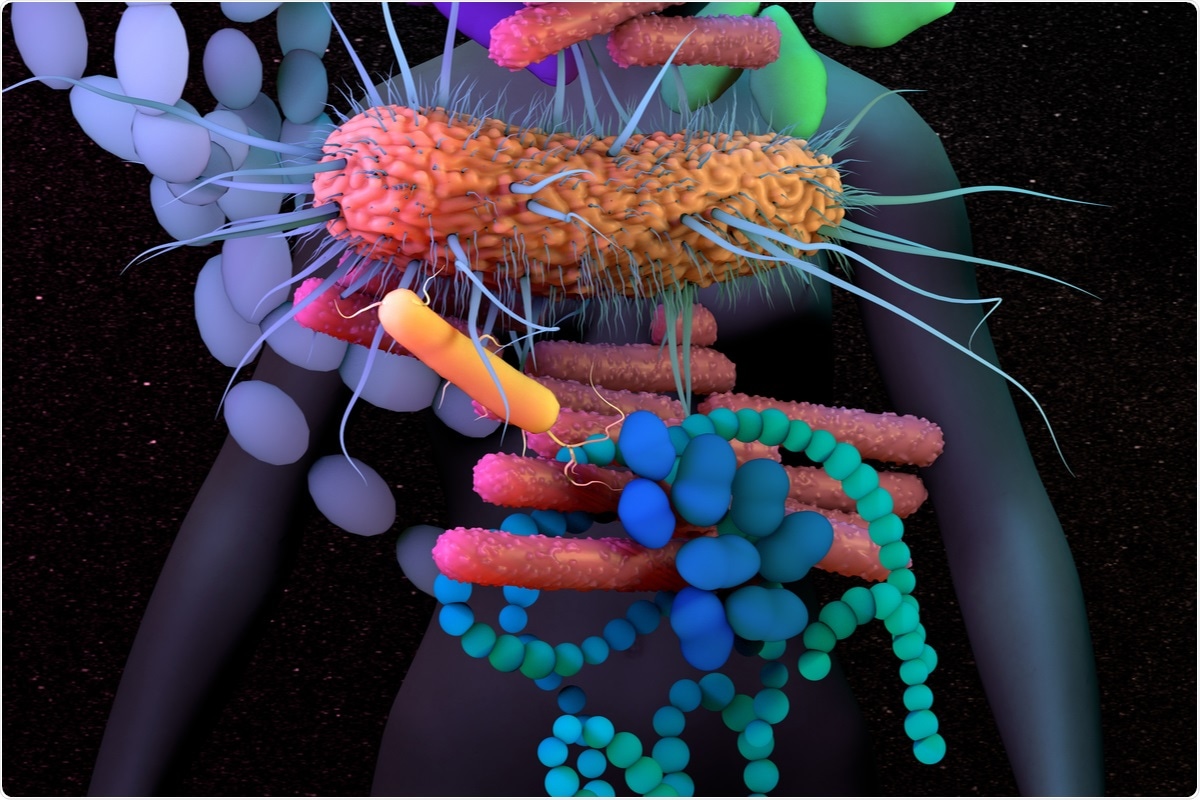

The body is full of colonies of harmless bacteria, fungi, and viruses called the microbiome. These species are beneficial to the body, aiding the body’s natural processes. There are more than 400 species of bacteria that make up the gut microbiome, helping digest food, ward off harmful pathogens, and synthesize vitamins.

Previous studies have noted that the gut microbiome has been present even in ancient people. This means that exploring the content of ancient people’s gut bacteria may offer new knowledge not only about their diet but also how they warded off diseases.

Health experts have also compared the gut microbiome of people from industrialized and non-industrialized regions.

Previous studies of children in Russia and Finland showed that those in industrialized regions were more likely to develop type 1 diabetes compared with those in non-industrialized areas.

These two groups of children had very diverse gut microbiome, highlighting that those who live in industrialized areas, the children are at a higher risk of developing not only type 1 diabetes but other autoimmune and allergic diseases.

Reconstructing ancient human gut microbiome

The team reconstructed ancient microbial genomes utilizing a set of eight paleofeces from 1,000 years to 2,000 years old discovered in the southwestern U.S. and Mexico. From there, they compared the ancient gut microbes to modern-day samples from both industrialized and non-industrialized populations.

In total, the researchers reconstructed 498 microbial genomes and concluded that 818 were from ancient individuals. Of these, 39 percent had not previously been found in the other samples.

The analyses were possible thanks to the extraordinary preservation of the paleofeces, the use of ancient deoxyribonucleic acid (aDNA) extraction methods for ancient feces, high sequencing depth, and the advances in de novo genome reconstruction methodology.

Compared with 789 present-day human gut microbiome samples from eight countries, the paleofeces samples were more similar to non-industrialized than industrialized human gut microbiomes.

Some of the food pieces found in the samples confirmed that the ancient people’s diet included beans and maize, which is typical of early North American farmers. In the Utah site, the team found a more eclectic, fiber-rich famine diet, including rice grass, pear, and grasshoppers in the sample’s food pieces.

After functional profiling, the team found a significantly lower abundance of antibiotic-resistance and mucin-degrading genes, including the enrichment of mobile genetic elements relative to industrial gut microbiomes. Plus, the ancient samples were more diverse, including dozens of previously unknown species.

This study facilitates the discovery and characterization of previously undescribed gut microorganisms from ancient microbiomes and the investigation of the evolutionary history of the human gut microbiota through genome reconstruction from paleofeces,” the researchers noted in the study.

The study also established that paleofeces with well-preserved DNA are abundant sources of microbial genomes. The previously undescribed microbial species in the ancient feces may shed light on the evolutionary histories of human microbiomes.

Future studies are needed to gain a better understanding of the human microbiome, which may help in discovering novel treatments for diseases such as type 1 diabetes and other autoimmune conditions. The studies may also help in developing approaches to restore the present-day gut microbiome to its ancestral state.

Source:

Journal reference:

Add Category

Add Category