Intel's Fab 42 in Chandler, Arizona

Stephen Shankland/CNETIntel has selected a 1,000-acre site in New Albany, Ohio, to be its third major US chipmaking location, with construction beginning this year and operations starting in 2025. Intel has committed to spend $20 billion on two chip fabrication facilities, or fabs, but ultimately expects a total of eight fabs in a plan that could reach $100 billion.

"Our expectation is that this becomes the largest silicon manufacturing location on the planet," CEO Pat Gelsinger told Time magazine.

In a press conference at the White House on Friday with Gelsinger, President Joe Biden called for Congress to pass legislation called the CHIPS Act that would grant chipmakers $52 billion in subsidies to help Intel and other chipmakers. "Let's do it for the sake of our economic competitiveness and our national security. Let's do it for the cities and towns all across America who are going to get their piece of the global economic package," Biden said. "American workers are going to stamp everything we can 'Made in America,' especially these computer chips."

The announcement is a centerpiece of Intel's effort to reclaim its chip technology lead and rejuvenate American manufacturing. Along with the new site on the outskirts of Columbus, Ohio, Intel also plans to build a second $100 billion "megafab" in Europe, but that decision is likely three or four months away, said Keyvan Esfarjani, who leads Intel manufacturing and operations.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. and South Korea's Samsung surged ahead when Intel's previously steady chip miniaturization progress faltered more than a half decade ago. Many top chip designers, including Qualcomm, AMD, Tesla and Apple, rely on TSMC to make their products. Intel, under the leadership of an engineer again with the return Gelsinger as chief executive, is trying to catch up to TSMC and Samsung by 2024 and surpass them in 2025.

The Ohio megafab will be at the heart of the effort. Intel for years concentrated manufacturing in Arizona and Oregon, and the new site will be a third major hub, with at least 3,000 employees in a state that's been hit hard by the US's waning influence in manufacturing. The US share of chipmaking business has dropped from 37% in 1990 to 12% today, according to the Semiconductor Industry Association, a trade group, but Gelsinger wants to bring that back to 30%.

Intel on Friday called this the largest private sector investment ever made in the state and said that it will spend a further $100 million on educational partnerships. It'll employ 7,000 construction workers during peak activity, and indeed the supply of those laborers was one factor that drew Intel to Ohio, Esfarjani said. Other factors include favorable tax treatment on expenses like property taxes, land availability, partnerships with universities and community colleges to train Ph.D.s and technicians, and ready connections to power, water and natural gas. Intel evaluated more than 35 sites before picking Ohio, he said.

The decline of manufacturing in Ohio in the 1970s and 1980s "decimated" the state, said Patrick Moorhead, an analyst at Moor Insights & Strategy. "Intel has a lot of work to do to build the ecosystem of the 500 vendors it will need and the accompanying skills," he tweeted.

Intel would get a boost from the CHIPS Act. Congress has yet to allocate the necessary funding, but if it did, it would cut about $3 billion off the price tag of a $10 billion fab, making the US competitive with government incentives in South Korea and Taiwan, Intel has said. Intel will proceed regardless of the CHIPS Act's progress, but the government subsidy will increase the size and speed of Intel's expansion, Esfarjani said.

"It is critically important to ensure that the CHIPS for America Act will pass through," he said. "It really sets the pace and the size for a project like this."

Biden blamed rising consumer prices in part on a global chip shortage that's slowed product shipments, especially cars, just as demand is soaring. Intel's new investments won't come in time to help allay today's shortage, but building US capacity will make the electronics supply chain more resilient, Biden said. That resilience is a key part of the Biden administration's support for the CHIPS Act.

The Senate has passed the CHIPS Act and funded it through the US Innovation and Competition Act (USICA), but the House hasn't yet followed. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi said Friday said the House of Representatives soon will get a competitiveness bill that "will supercharge our investment in chips."

'Ballooning' Intel spending

Gelsinger returned to Intel last year after more than a decade away on the condition that the board support his plans for Intel's recovery, which includes massive spending on new chipmaking capacity, he told CNET in an earlier interview.

It's tough to stay at the cutting edge of chipmaking, as evidenced by decisions in recent years by IBM and GlobalFoundries to no longer stay at the front of the pack. Chipmaking rewards high volume, where large-scale operations can justify the costs of developing advancements and building fabs.

Engineers like Intel's restored tech focus, but the company has plenty of convincing to do. Sanford Bernstein analyst Stacy Ragson has a negative rating on the stock as Intel tries to steer a new course "to atone for 10 years of sin." In a report from earlier in January, he complained of Intel's "ballooning" capital expenditures, declining profit margins, likely future losses in market share and "an aggressive roadmap fraught with risk, with outlandish growth targets."

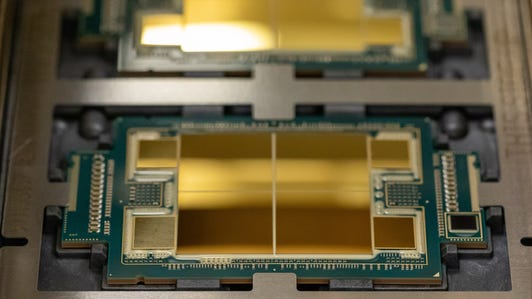

Fabs are enormously expensive. The newest machines to inscribe electronic circuitry onto silicon wafers at the smallest scales are expected to sell for $340 million each on average, according to their maker, ASML. Intel is the first buyer of a next-generation machine, but learning how to use it effectively, an area where Intel lags Samsung and TSMC, will take time. TSMC plans to spend $40 billion to $44 billion on new fabs in 2022 alone.

Gelsinger detailed a plan to accelerate Intel manufacturing progress, with upgrades coming roughly annually. The most advanced "node" the company disclosed on this manufacturing process road map is called Intel 18A. The Ohio site will manufacture chips with Intel 18A or a more advanced process, according to Esfarjani.

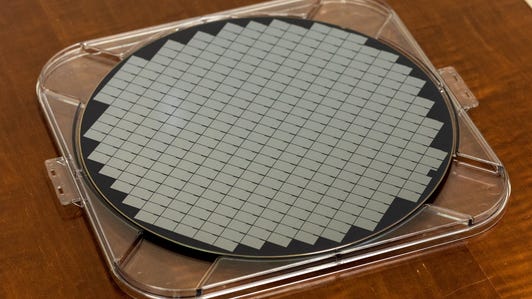

The Ohio site will significantly increase Intel capacity. Chips are inscribed on silicon crystal wafers 300mm (about 1 foot) in diameter, with dozens or hundreds of chips on each wafer depending on the chip size. Each Intel fab typically processes 4,000 to 6,000 wafers per week, Esfarjani said.

Fab investment's economic ripple effects

Chipmaking isn't just a lucrative business for the company doing the manufacturing. It also means money for a constellation of other companies that supply fabs and that package their products into electronics.

As occurred with its Oregon and Arizona operations, Intel expects a surge of supporting businesses to join it in Ohio.

"We start pretty much with nothing, and we build this city, the ecosystem [of] vendors and suppliers and the partners," Esfarjani said. "Already we are getting a lot of excitement from our suppliers. They're all in, and they're ready to come as well."

With processors crucial to everything from washing machines and cars to military aircraft and schools, CHIPS Act proponents want to keep the US from being reliant on overseas companies for semiconductor manufacturing. The global chip shortage, triggered by the COVID-19 pandemic, has revealed how many industries are crippled when they can't ensure supply. Part of Gelsinger's recovery plan for Intel is to build chips for others, not just itself, with a new business unit called Intel Foundry Services.

It's not yet clear how much the Ohio fabs capacity will go to Intel and how much will go to foundry customers, but trying to increase capacity is critical

"Right now, our problem is, more of a demand side," Esfarjani said. "We need to make more than what we have."

Add Category

Add Category