A special fiber could bring our clothing to life.

Fink Lab MIT/Elizabeth Meiklejohn RISD/Greg HrenWearable tech is extending far beyond Apple Watches and FitBits. Reimagining pants, T-shirts and jackets as having multiple purposes, scientists have invented an "acoustic fabric" that can detect and produce sound.

Potentially, clothes made of this material could continuously monitor our heart or respiratory rate in real time by picking up vibrations on our skin, offer us the option to answer phone calls and communicate through our garb, and function as a sort of hearing aid to help those with hearing loss navigate noisy environments.

In addition, the fabric "can be integrated with spacecraft skin to listen to [accumulating] space dust or embedded into buildings to detect cracks or strains," Wei Yan, an assistant professor at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore and lead author of a study on the cloth published Wednesday in the journal Nature, said in a statement. "It can even be woven into a smart net to monitor fish in the ocean."

Smart fabric products, like the team's acoustic cloth, are relatively new engineering endeavors that have been picking up over the last several years. For instance, we've seen the rise of items like color-changing clothing and material that can "sweat" like human skin. These involve innovative techniques like smartphone app compatibility and complex microfluidic platforms, respectively.

Here's how the new sound-related material works.

A flexible fiber made of piezoelectric material, which is a substance sensitive to electrical signals, is woven into fabric. The clothes we wear already pick up sound vibrations in our vicinity, but we can't really perceive them because the rumbles operate on scales of nanometers. That's where the team's fiber comes in.

It captures these minute vibrations and converts them into electrical signals, which are then recorded on a device for later inspection. The researchers say their design was inspired by the way human ears work, which involves a similar vibration-to-signal conversion process, though calls for an extra step that deals with pressure.

As proof of principle, the team exposed a garment woven with the special fiber to a range of sound vibrations, such as those from a quiet library or heavy traffic. It successfully converted the vibrations -- indiscernible by humans -- into the appropriate electrical signals.

"This shows that the performance of the fiber on the membrane is comparable to a handheld microphone," Grace Noel, co-author of the study and a researcher at MIT, said in a statement. On the flip side, the team also decided to see whether the fabric can be reverse-engineered not only to detect sound vibrations and convert them into usable electrical data but also to operate as a speaker that translates electrical data back into vibrations we can hear.

The researchers recorded a string of words and fed the recording into the fiber with applied voltage power. Lo and behold, the garment took the electrical signal and converted it the opposite way -- playing back sound vibrations that our ears can detect. But the team didn't stop there.

They carried out more experiments to really see how far this fabric can stretch. Two were especially notable.

The first involved the researchers sewing the fabric onto the back of a shirt, then clapping their hands while standing in various positions. The idea was to see if the cloth panel could pick up which direction the sound was coming from. It did. "The fabric was able to detect the angle of the sound to within 1 degree at a distance of 3 meters away," Noel said.

Next up, the team stitched a single fiber to the shirt's inner lining, over the chest region, and had a healthy volunteer wear the garment. As expected, it accurately monitored the volunteer's heartbeat. Strikingly, the study notes that pretty much any fabric woven with the fiber doesn't become heavy or filled with lofty wires.

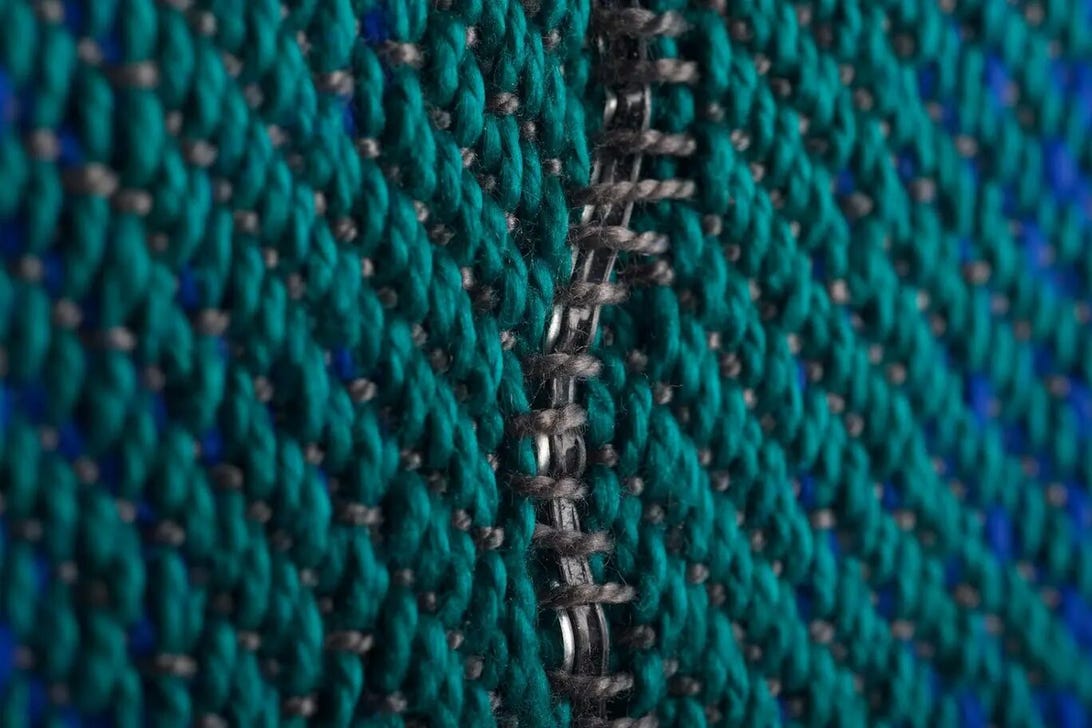

"It feels almost like a lightweight jacket -- lighter than denim, but heavier than a dress shirt," study co-author Elizabeth Meiklejohn, a graduate student at the Rhode Island School of Design who wove the fabric using a standard loom, said in a statement.

Better yet: It's machine washable.

"The learnings of this research offers quite literally a new way for fabrics to listen to our body and to the surrounding environment," said Yoel Fink, a researcher at MIT and co-author of the study. "The dedication of our students, postdocs and staff to advancing research which has always marveled me is especially relevant to this work, which was carried out during the pandemic."

Add Category

Add Category