If NASA's collection of more than 5,000 exoplanets were a zoo, you'd find Jupiter doppelgangers at every corner and worlds with waterless rain decking the entrance. You'd stumble upon hellish landscapes behind barren paths and maybe a pop-up exhibit of an ocean planet born of Poseidon's reveries. But if this zoo really imitated life, you'd probably see most scientists shuffling into a room with all the "normal-sounding" planets. Spots that seem kind of like Earth, places most plausible to sustain life. (Well, life as we know it, at least).

NASA's exoplanet division, for instance, calls Trappist-1 the most studied planetary system, aside from our own. It's very Earth-y, containing seven rocky worlds with the potential to hold water.

"It is important to detect as many temperate terrestrial worlds as possible to study the diversity of exoplanet climates, and eventually to be in a position to measure how frequently biology has emerged in the cosmos," Amary Triaud, a professor of exoplanetology at the University of Birmingham, said in a statement.

As such, on Wednesday, Triaud, along with a crew of international astronomers, reported the exciting detection of two more

temperate, terrestrial muses to explore. Some 100 light-years from Earth, this planetary pair orbits a star dubbed Speculoos-2 -- yes, like the biscuit -- named for the telescopes that determined their existence: the Search for Habitable Planets Eclipsing Ultra-cool Stars project. Details of the researchers' results will be published in a forthcoming edition of the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

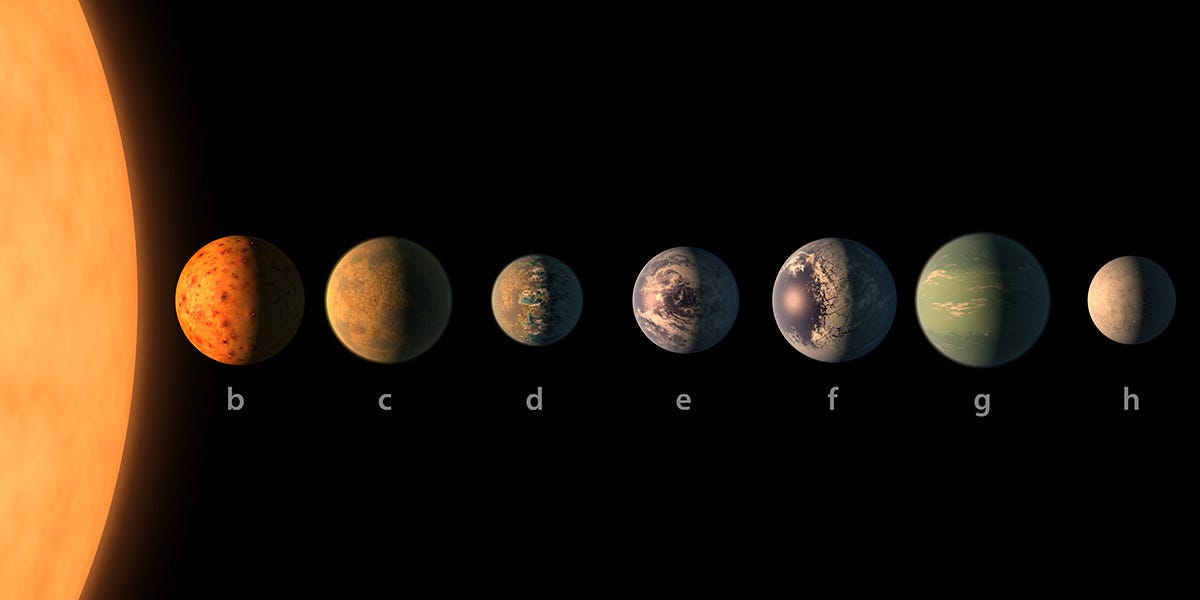

A line up of Trappist-1 planets from Trappist-1b in closest orbit to the star to Trappist-1h. Trappist-1e, f and g are thought to have the best chance of supporting life.

NASA-JPL/Caltech"The goal of Speculoos is to search for potentially habitable terrestrial planets transiting some of the smallest and coolest stars in the solar neighborhood, such as the Trappist-1 planetary system, which we discovered in 2016," Michaël Gillon, of the University of Liege and principal investigator of the Speculoos project, said in a statement. "Such planets are particularly well suited to detailed studies of their atmospheres and to the search for possible chemical traces of life with large observatories, such as the James Webb Space Telescope."

According to the new study's researchers, one of the two worlds had already been identified by NASA's Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite, but it wasn't until Speculoos stepped in that scientists gained 100% certainty this planet was, indeed, a planet.

Then, after some analysis, the team concluded the world, named LP 890-9b, is about 30% larger than Earth and completes an orbit around its shared star, every 2.7 days.

"A follow-up with ground-based telescopes is often necessary to confirm the planetary nature of the detected candidates and to refine the measurements of their sizes and orbital properties," Laetitia Delrez, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Liège and lead author of the article, said in a statement.

Basking under the soft light of the Chilean skies are two domes of the Speculoos Southern Observatory. Comprising four domes, Speculoos is located at the European Southern Observatory's Paranal Observatory, which is near the Very Large Telescope.

ESO/G. LambertThe other planet, named LP 890-9c, was a little more mysterious. It was previously unknown. But after some testing and data sifting, the team figured the world is about 40% larger than Earth and has an orbital period of about 8.5 days -- a bit longer than its sibling's.

That orbital period is quite exciting, though, because the researchers say it means the exoplanet is physically located in its star's "habitable zone." The habitable zone simply refers to the region around a star that's not too hot nor too cold to sustain liquid water for billions of years. Sometimes, the range is aptly referred to as the Goldilocks zone. "This gives us a license to observe more and find out whether the planet has an atmosphere, and if so, to study its content and assess its habitability," Triaud said.

Hopefully, if NASA's Webb telescope can decode some of that information, it will unveil an answer to the biggest question of all: Are we totally alone in the cosmos?

But, don't get too hyped up. That's likely a long way from now. You can find me at the exoplanet zoo until then, probably checking out the nonspherical planet exhibit. This one's shaped like a rugby ball. Is that not the weirdest thing?

Add Category

Add Category