Visiting a friend in Silicon Valley in December, I drove by a local landmark just around the corner: Steve Jobs' boyhood home. The modest ranch-style house doesn't stand out much from other homes on the block, but it represents technology history. In that very garage, in the '70s, Jobs and Apple co-founder Steve Wozniak put together the first 50 Apple I 8-bit desktop computers. That machine, Apple's first product, went on sale in July 1976 for $666.66.

It's stunning to think of the history-making coding and conversations that went on in that single-story home, and I felt a rush of amazement as I slowed down and imagined Jobs and Woz hunched over a garage workbench, analyzing semiconductor chips. I had a similar response when scrolling through the newly scanned first six issues of the Homebrew Computer Club newsletter on Arkive, a nascent global community that aims to decentralize art by allowing anyone to acquire and vote for items that enter its collections. It calls itself a "museum curated by the people," and the newsletters count among its early acquisitions. Arkive shared word of the newsletters' procurement with CNET exclusively.

The fifth issue of the Homebrew Computer Club newsletter.

ArkiveThe influential Homebrew computer hobbyist group brought together members to swap ideas, code and hardware. Many members would go on to become tech pioneers, including Jobs; Wozniak; Lee Felsenstein, who created the world's first mass-produced portable computer, the Osborne; and Len Shustek, an early developer of PC networks and founding chairman emeritus of the Computer History Museum. The newsletter's pages capture the early days of the personal-computer revolution and the spirit of its innovating, influential times.

The first issue, published just 10 days after the club's initial meeting on March 5, 1975, contains treasures. There's a list with names, addresses and interests of new members. Several note owning an Altair 8800, a microcomputer designed in 1974 by Micro Instrumentation and Telemetry Systems and sold to hobbyists in a kit, while others mention they have an Intel 8008, an early 8-bit programmable microprocessor.

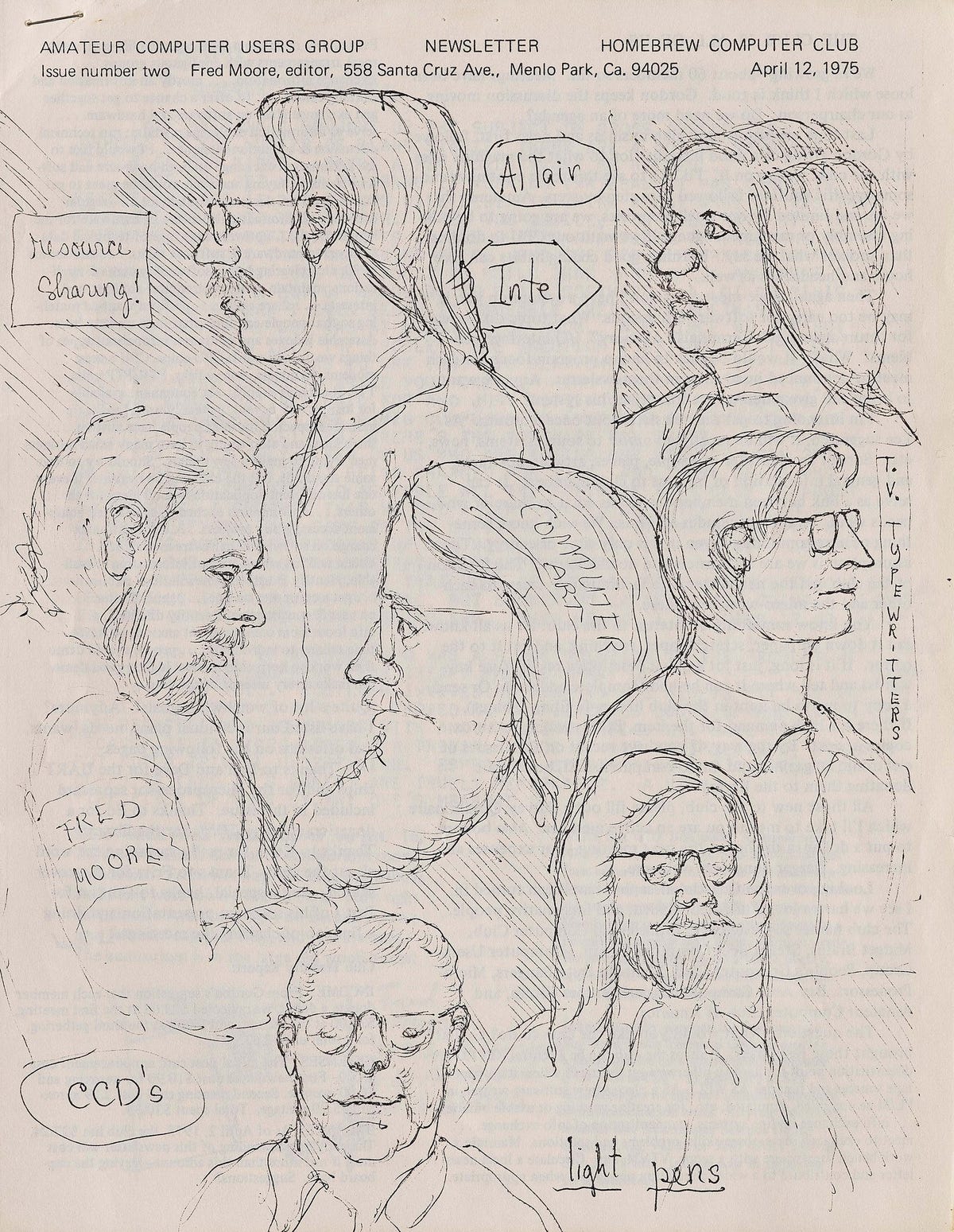

Issue 2 of the Homebrew Computer Club newsletter includes this priceless drawing of some of its members.

ArkiveNotes from the first get-together indicate lively speculation about what people would eventually do with home computers.

"We asked that question and the variety of responses show that the imagination of people has been underestimated," the newsletter reads. "Uses ranged from the private secretary functions: text editing, mass storage, memory, etc., to control of house utilities: heating, alarms, sprinkler system, auto tune-up, cooking, etc., to GAMES..."

Issue 2 contains a microprocessor scorecard and a great hand-drawn portrait of seven of the club's members, some rocking distinctly '70s hair and glasses. A list of local supply stores notes which ones take mail and phone orders. Early contenders for club name, I learned, included "Eight-Bit Byte Bangers."

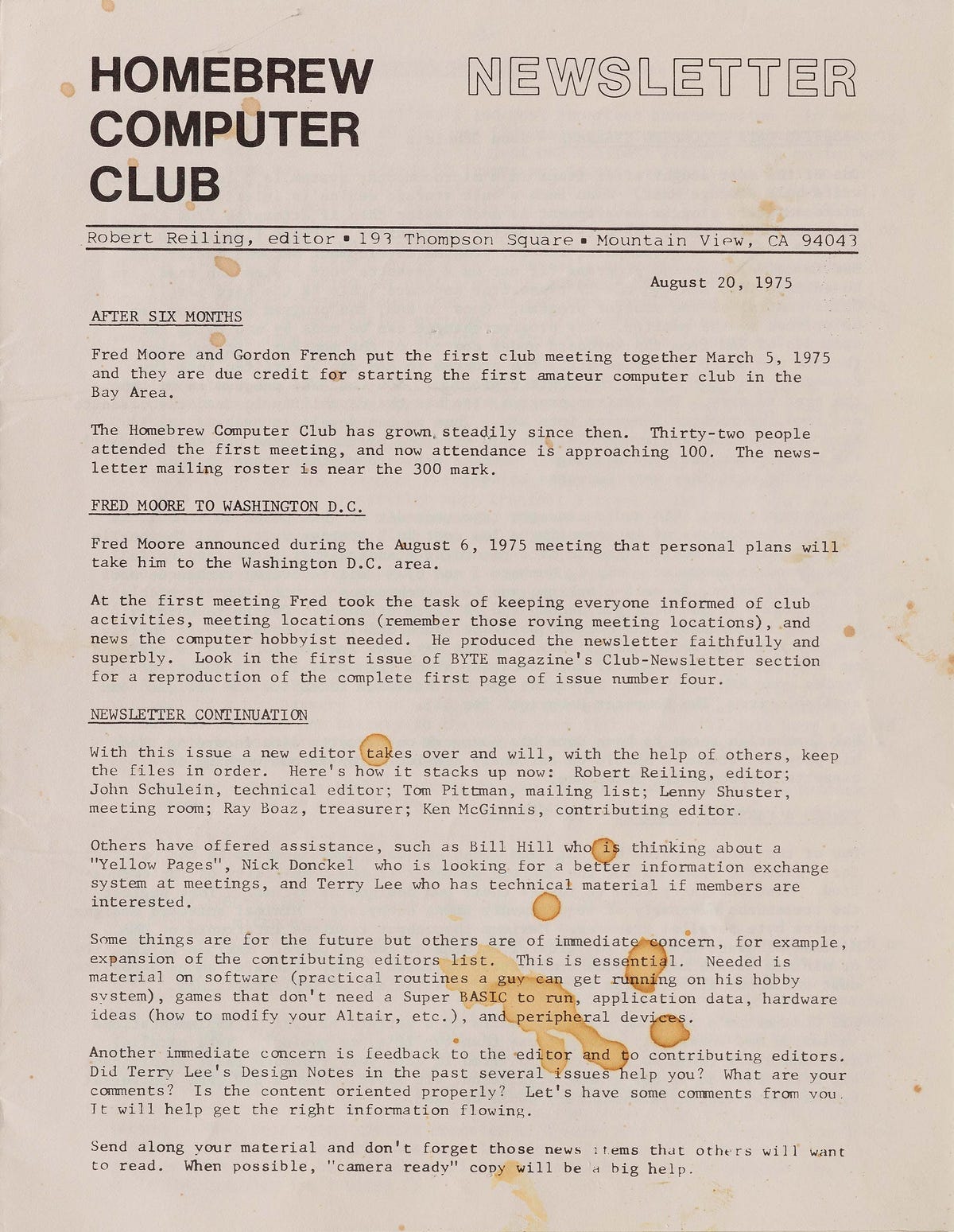

It's possible to thumb through online versions of the typewritten newsletter elsewhere online -- on the Computer History Museum's site for example -- but the ones at Arkive preserve extra details that really bring the artifacts to life: 10-cent stamps, smudged postmarks, passages underlined in green pen, and coffee stains, so many coffee stains, on the pages.

Created by the club's Lee Felsenstein, the Osborne was the world's first mass-produced portable computer. It's pictured here in 2013, at a reunion of the famous club 38 years after its first meeting.

Daniel Terdiman/CNETArkive's 1,500 members include artists; private art dealers; former museum curators; Web3 experts; coders; and others who believe anyone should be able to help define and amplify culturally significant items. The team debuted its first collection, titled "When Technology Was a Game Changer," at Art Basel Miami Beach in December. The collection includes objects "that reflect, embody and witness turning points in art or culture driven by technological advances."

In addition to the scanned Homebrew Computer Club newsletters, there's the 188-page patent for the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer, or ENIAC, the first programmable general-purpose electronic digital computer, which was built during World War II.

Fast Company global technology editor Harry McCracken once called the Homebrew Computer Club "the crucible for an entire industry," and Arkive's members clearly appreciate the value of the newsletter's weathered pages. "It's a beautiful and humbling reminder that technology would not exist without community and human connection," one said in explaining its cultural significance. Said another: "Their tinkering, hopeful, super badass good-guy giga-nerd spirit lives on."

A page from the sixth issue of the Homebrew Computer Club, preserved with coffee stains.

Arkive

Add Category

Add Category